Cleft Lip

Topic Overview

What is cleft lip?

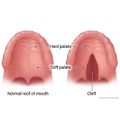

Cleft lip is a treatable birth defect. It happens when the tissues of the upper jaw and nose don’t join as expected during fetal development. This causes a split (cleft) in the lip.

A cleft lip may be complete or incomplete. With either type, it may involve one or both sides of the upper lip and rarely occurs in the lower lip. Cleft lip often occurs with cleft palate. Cleft palate and cleft lip are the most common birth defects of the head and neck.

A cleft lip usually doesn’t cause health problems. Surgery can be done to fix the split and improve the appearance of the mouth and nose.

What causes cleft lip?

Doctors don’t know what all of the causes are. But your baby may be more likely to have a cleft lip if:

- You use certain medicines while you’re pregnant.

- You use alcohol or illegal drugs while you’re pregnant.

- You or a household member smokes while you’re pregnant.

- You are exposed to radiation or infections while you’re pregnant.

- You or your baby’s father have a family history of cleft lip.

It’s important to take good care of yourself before and during your pregnancy so that your baby will be as healthy as possible.

People who have a family history of cleft lip may want to think about genetic counseling. It can help you understand your chances of having a child with a cleft lip.

What are the symptoms?

You’ll notice a split in the baby’s lip. It’s easy to see right at birth.

A baby with a cleft lip typically doesn’t have any problems feeding. But a baby who has both a cleft lip and a cleft palate may have feeding problems.

How is a cleft lip diagnosed?

A cleft lip is usually diagnosed at birth. Shortly after birth, the baby will have a physical exam. The doctor will look inside your baby’s mouth to see whether there is also a cleft palate.

Sometimes a fetal ultrasound during pregnancy can detect a cleft lip. But an ultrasound doesn’t always find the problem, so doctors can’t always rely on it to diagnose a cleft lip.

How is it treated?

Surgery can fix a cleft lip. Before surgery, a baby may wear a mouth support (such as a dental splint) or a soft dental molding insert along with medical adhesive tape.

Most doctors suggest that surgery be done by the time a baby is 6 months old.footnote 1 But the timing of the surgery depends on a few things, such as how severe the split is and the health of the baby.

As your child grows, he or she will probably need more than one operation. For example, if your baby’s nose has an odd shape, surgery may help fix it. Your child may need other treatment, such as speech therapy if he or she has a hard time pronouncing words.

What can you do at home to help your child and yourself?

As your child grows, pay special attention to dental care and any speech problems. Support your child’s self-esteem. Explain how cleft lips form and how having one has been a part of making your child strong. This will help your child know how to answer questions from other children and adults. You can also ask your doctor what treatments can make the scar less noticeable.

Caring for your child who has a cleft lip can take time and patience. Seek support from friends and family. You can join a support group to meet others who are going through similar challenges.

References

Citations

- Porter RS, et al., eds. (2011). Congenital craniofacial and musculoskeletal abnormalities. In Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, 19th ed., pp. 2969–2975. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp.

Other Works Consulted

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2003, reaffirmed 2011). Neural tube defects. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 44. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 102(1): 203–210.

- Edwards SP, et al. (2007). Cleft lip and palate. In DM Laskin, AO Abubaker, eds., Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, pp. 135–151. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing.

- Hoffman WY (2012). Cleft lip and palate. In AK Lalwani, ed., Current Diagnosis and Treatment in Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, 3rd ed., pp. 345–361. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Klein U (2014). Oral medicine and dentistry. In WW Hay Jr et al., eds., Current Diagnosis and Treatment: Pediatrics, 21st ed., pp. 490–501. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Mossey PA, et al. (2009). Cleft lip and palate. Lancet, 374(9703): 1773–1785.

- Rowe LD (2009). Congenital disorders of the oral cavity and lip section of Congenital anomalies of the head and neck. In JB Snow Jr, PA Wackym, eds., Ballenger’s Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 17th ed., pp. 835–838. Hamilton, ON: BC Decker.

- Shi M, et al. (2007). Orofacial cleft risk is increased with maternal smoking and specific detoxification-gene variants. American Journal of Human Genetics, 80(1): 76–90.

- Wilcox AJ, et al. (2007). Folic acid supplements and risk of facial clefts: National population based case-control study. BMJ. Published online January 26, 2007 (doi:10.1136/bmj.39079.618287.0B).

Current as of: December 12, 2018

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:John Pope, MD, MPH – Pediatrics & Kathleen Romito, MD – Family Medicine & Adam D. Schaffner, MD, FACS – Plastic Surgery, Otolaryngology

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.