Living With a Spinal Cord Injury

Topic Overview

What is a spinal cord injury?

A spinal cord injury is damage to the spinal cord. The spinal cord is a soft bundle of nerves that extends from the base of the brain to the lower back. It runs through the spinal canal, a tunnel formed by holes in the bones of the spine. The bony spine helps protect the spinal cord.

The spinal cord carries messages between the brain and the rest of the body. These messages allow you to move and to feel touch, among other things. A spinal cord injury stops the flow of messages below the site of the injury. The closer the injury is to the brain, the more of the body is affected.

- Injury to the middle of the back usually affects the legs (paraplegia).

- Injury to the neck can affect the arms, chest, and legs (quadriplegia).

A spinal cord injury may be complete or incomplete. A person with a complete injury doesn’t have any feeling or movement below the level of the injury. In an incomplete injury, the person still has some feeling or movement in the affected area.

What causes a spinal cord injury?

A spinal cord injury usually happens because of a sudden severe blow to the spine. Often this is the result of a car accident, fall, gunshot, or sporting accident. Sometimes the spinal cord is damaged by infection or spinal stenosis, or by a birth defect, such as spina bifida.

What happens after a spinal cord injury?

At the hospital, treatment starts right away to prevent more damage to the spine and spinal cord. Steps are taken to get your blood pressure stable and help you breathe. You may get a steroid medicine to reduce swelling of the spinal cord. A computed tomography scan (CT scan) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be done right away to help find out how bad the injury is.

You will be tested to see how you respond to pinpricks and light touch all over your body. The doctor will ask you to move different parts of your body and test the strength of your muscles. These tests help the doctor know how severe the injury is and how likely it is that you could get back some feeling and movement. Most recovery occurs in the first 6 months.

As soon as you are stable, rehabilitation (rehab) starts. The goal of rehab is to help prepare you for life after rehab and help you be as independent as possible. What happens in rehab depends on your level of injury. The rehab team will help you to learn how to:

- Prevent problems like pressure injuries and know when you need to call a doctor.

- Exercise to keep your muscles strong and flexible.

- Eat a balanced diet to help you stay healthy and manage your weight.

- Learn to do things that most people do without thinking, such as managing your bladder and bowel.

- Use a wheelchair or other devices so you can do things you enjoy.

You may have follow-up tests to monitor your condition over time. These may include a bladder test, an X-ray of the spine, CT scan, MRI, and a bone density test.

There is a lot to learn, and it may seem overwhelming at times. But with practice and support, it will get easier.

What is life like with a spinal cord injury?

Having a spinal cord injury changes some things forever, but you can still have a full and rewarding life. A saying among people who have a spinal cord injury is, “Before your injury, you could do 10,000 things. Now you can do 9,000. So are you going to worry about the 1,000 things you can’t do or focus on the 9,000 things you can do?”

After they adjust, many people with spinal cord injuries are able to work, drive, play sports, and have relationships and families. Your rehab team can provide the support, training, and resources to help you move toward new goals. It’s up to you to make the most of what they have to offer.

Adapting to life with a spinal cord injury can be tough. You can expect to feel sad or angry at times or to grieve for your lost abilities. It is important to express these feelings so they don’t keep you from moving ahead. Talk with family and friends, find a support group, or connect with others online. Talking to other people who have spinal cord injuries can be a big help.

It’s hard to enjoy life if you have ongoing pain or depression. If you do, tell your doctor. There are medicines and other treatments that can help.

Caring for a person who has a spinal cord injury can be both rewarding and difficult. If you help take care of someone who has a spinal cord injury, don’t forget to take care of yourself too. Find a local support group, and make time to do things you enjoy.

What Happens

Often a spinal cord injury (SCI) is caused by a blow to the spine, resulting in broken or dislocated bones of the spine (vertebrae). The vertebrae bruise or tear the spinal cord, damaging nerve cells.

When the nerve cells are damaged, messages cannot travel back and forth between the brain and the rest of the body. This causes a complete or partial loss of movement (paralysis) and feeling.

Sometimes the spinal cord is damaged by infection, bleeding into the space around the spinal cord, spinal stenosis, or a birth defect, such as spina bifida.

At the hospital

A person with a potential SCI is taken to an emergency department and then to an intensive care unit. The first priority is stabilizing blood pressure and lung function, as well as the spine, to prevent further damage. When a spinal cord injury is caused by a serious accident, treatment for other injuries is often needed.

A computed tomography scan (CT scan) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be done right away to help find out how bad the injury is. These provide detailed images of the spine.

You will be tested to see how you respond to pinpricks and light touch all over your body. The doctor will ask you to move different parts of your body and test the strength of your muscles.

Classifying a spinal cord injury

An SCI can be classified based on how much feeling and movement you have or where the damage occurred. When a nerve in the spinal cord is injured, the nerve location and number are often used to describe how much damage there is.

The vertebrae and spinal nerves are organized into segments, starting at the top of the spinal cord. Within each segment they are numbered.

People with SCIs often use a segment of the spine to talk about their functional level. (Your functional level is how much of your body you can move and feel.) For example, you might describe yourself as a “C7.”

The nerves around a vertebra control specific parts of the body. Paralysis occurs in the areas of the body that are controlled by the nerves associated with the damaged vertebrae and the nerves below the damaged vertebrae. The higher the injury on the spinal cord, the more paralysis there is.

- Damage to the spinal nerves in the neck can cause paralysis of the chest, arms, and legs (tetraplegia, also known as quadriplegia).

- Damage lower down on the spine (thoracic, lumbar, or sacral segments) can cause paralysis of the legs and lower body (paraplegia).

- Breathing is only affected by injuries high on the spinal cord.

- Bowel and bladder control can be affected no matter where the spinal cord is injured.

Damage to the spinal cord can be complete or incomplete.

- In a complete SCI, you do not have feeling or voluntary movement of the areas of your body that are controlled by your lowest sacral nerves—S4 and S5. These nerves control feeling and movement of your anus and perineum.

- In an incomplete SCI, you have varying amounts of movement and feeling of the areas of your body controlled by the sacral nerves.

Some recovery of feeling and movement may return after the injury—how much depends on the level of injury, the strength of your muscles, and whether the injury is complete or incomplete. Most recovery occurs within the first 6 months of the injury.

For the family and caregivers

After a traumatic SCI, your loved ones will often ask questions about the injury and what it means. Keep your answers short, simple, and honest. You cannot give a complete answer, because it’s often hard to know how serious the injury is and how much you will recover. This typically is not known until swelling and bleeding are reduced and the doctors can find out where the spinal cord has been injured.

Moving into rehab

After emergency treatment and stabilization, you will move into rehab. A rehab center helps you adjust to life, both physically and emotionally. The goal of rehab is to help you be as independent as possible.

Your rehab depends on your level of injury. You may have to learn how to manage your bowel and bladder, walk with crutches, do breathing exercises, and move between a wheelchair and another location.

Follow-up tests

As part of your long-term care, you may need to have follow-up tests over time. These may include:

- A bladder test. This measures your bladder function and size.

- A spinal X-ray. This monitors your spine’s condition.

- A computed tomography scan (CT scan) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These provide detailed pictures of the spine.

- A bone density test. This measures the minerals (such as calcium) in your bones using a special X-ray, a CT scan, or ultrasound.

Rehabilitation

As soon as you are stabilized after your spinal cord injury (SCI), your transition into rehabilitation (rehab) begins. The initial focus of rehab is to prevent complications related to your SCI and for you to relearn how to do daily functions, sometimes by using different muscle groups.

Rehab centers help you adjust—physically and emotionally—to life with less mobility and feeling than you previously had. What rehab does depends on which part of your spine was injured. Rehab can include learning how to:

- Prevent complications related to your spinal cord injury by managing bowel and bladder function and building strength, endurance, and flexibility. You may also learn how to handle problems such as pressure injuries, urinary tract infections, and muscle spasticity.

- Do daily tasks, such as cook, brush your teeth, and move from a wheelchair to a bed or chair.

- Prepare for life after rehab by learning to cope with your feelings, communicate your needs, and be physically and emotionally intimate.

Rehab centers

Rehab for an SCI generally takes place in a special center. You and your family work with a rehab team, which includes your doctor, rehab nurses, and specialists such as physical and occupational therapists. Your rehab team designs a unique plan for your recovery that will help you recover as much function as possible, prevent complications, and help you live as independently as possible.

Choosing the right rehab center is important. Be sure that you choose one that meets your specific needs. Before choosing a rehab center, ask questions about its staff, accreditation, and activities, and how it transitions you back into your community.

Bladder Care

Good bladder management can improve your quality of life by preventing bladder problems, which is one of the biggest concerns for people who have spinal cord injuries (SCIs).

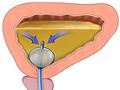

Normally, the kidneys filter waste products and water from the blood to form urine, which is stored in the bladder. When the bladder is full, a message is sent from the bladder to the brain. The brain sends a message back to the bladder to squeeze the bladder muscle and relax the sphincter muscles that control the flow of urine. After the bladder starts to empty, it normally empties all of the urine.

After an SCI, the kidneys usually continue to filter waste, and urine is stored in the bladder. But messages may not be able to move between your bladder and sphincter muscles and your brain. This can result in the:

- Inability to store urine. You cannot control when your bladder empties (reflex incontinence). This is known as reflex or spastic bladder.

- Inability to empty the bladder. Your bladder is full, but you can’t empty it. It stretches as it continues to fill with urine, which can cause damage to the bladder and kidneys. This is known as a flaccid bladder.

Not taking good care of your bladder can lead to urinary tract infections (UTIs), kidney and bladder problems, sepsis (a bloodstream infection), and, in rare cases, kidney failure. For information on testing for, treating, and preventing UTIs, see the topic Urinary Tract Infections in Teens and Adults.

Bladder programs

A bladder management program lets you or a caregiver empty your bladder when it is easy for you and helps you avoid bladder accidents and prevent UTIs. You and your rehabilitation team decide which bladder management program is best for you. You need to consider where your spinal cord is injured and how it has affected your bladder function. You also need to consider your lifestyle, how likely you are to get bladder infections, and whether you or a caregiver is able to use a catheter.

The most important things in bladder management are monitoring the amount of fluids you drink, following a regular schedule for emptying your bladder, and being sure that you empty your bladder completely. Your rehab team will help you set up a schedule based on your needs and the amount of fluids you typically drink.

Common ways to manage bladder function include the following:

- Intermittent catheterization programs (ICPs) are often used when you have the ability to use a catheter yourself or someone can do it for you. You insert the catheter—a thin, flexible, hollow tube—through the urethra into the bladder and allow the urine to drain out. It is done at scheduled times, and the catheter isn’t permanent.

- If you can’t use intermittent catheterization, you can use a permanent catheter known as an indwelling Foley catheter. Urinary tract infections are more likely to occur with long-term use of an indwelling catheter than with an ICP. Caring for the catheter is important to avoid infections.

- If you use an indwelling Foley catheter, after a period of time you may be able to change to a suprapubic indwelling catheter. This is a permanent catheter that is surgically inserted above the pubic bone directly into the bladder. It does not go through the urethra.

- If you can’t use intermittent catheterization and can’t (or don’t want to) use an indwelling catheter, you may be able to choose surgery that creates a urostomy. An opening (stoma) is made between your bladder and the skin of your belly. Urine then drains into a bag attached to your skin at the stoma. Intermittent catheterization can be used through the stoma, if needed.

- For men, a condom catheter can also be used. Condom catheters are only for short-term use, because long-term use increases the risk of urinary tract infections, damage to the penis from friction with the condom, and a block in the urethra.

- If you have a spastic bladder, you may be able to “trigger” the bladder to contract and avoid having to use a catheter. To do this, you can try tapping on the bladder area, stroking your thigh, or doing push-ups in your wheelchair. Or you can use Valsalva maneuvers, which are efforts to breathe out without letting air escape through the nose or mouth.

- It is also possible to use absorbent products, such as adult diapers.

You may use just one method or a combination.

Medicines

A number of medicines are available to help you manage your bladder. These include:

- Anticholinergics, such as oxybutynin and propantheline, which calm the bladder muscles. They may prevent uncontrollable bladder spasms that force urine out of the bladder.

- Cholinergics, such as bethanechol, which can help the bladder to squeeze, forcing out urine. When cholinergics are used, other medicines may also be used to help relax the muscles that hold urine in the bladder. These include alpha-blockers (for example, terazosin) and botulinum toxin.

Research continues on bladder management. New methods include surgically implanted components that stimulate the bladder through a radio control.

Note: Bladder problems can trigger autonomic dysreflexia, which causes sudden very high blood pressure and headaches. If not treated promptly and correctly, it may lead to seizures, stroke, and even death. These complications are rare, but it’s important to know the symptoms and watch for them.

Bowel Care

You or a caregiver can manage your bowel problems to prevent unplanned bowel movements, constipation, and diarrhea. Although this often seems overwhelming at first, knowing what to do and establishing a pattern makes bowel care easier and reduces your risk of accidents.

A spinal cord injury generally affects the process of eliminating waste from the intestines, causing a:

- Reflexive bowel. This means you cannot control when a bowel movement occurs.

- Flaccid bowel. This means you can’t have a bowel movement. If stool remains in the rectum, mucus and fluid will sometimes leak out around the stool and out the anus. This is called fecal incontinence.

Bowel programs

When choosing a way to deal with bowel problems, you and your rehab team will discuss such things as the type of bowel problem you have, your diet, whether you or a caregiver will do the program, and any medicines that may affect your program.

- For a reflexive bowel, you may use a stool softener, a suppository to trigger the bowel movement, and/or stimulation with your finger (digital stimulation). There are many stool softeners and suppositories available. You will have to experiment to find what works best for you.

- For a flaccid bowel, you may use digital stimulation and manual removal of the stool. At first, you do this program every other day. Later, you may need to do it more often to prevent accidents. You may also have to adjust how much and when you eat.

- Eating more fiber can help some people who have spinal cord injuries manage their bowel habits. Good sources of fiber include whole-grain breads and cereals, fruits, and vegetables.

For best results:

- Do your program at the same time every day. Most people do their bowel program in the morning. Doing it after a meal can take advantage of a natural bowel reflex that happens after eating. Choose the most convenient time for you, and stay with it.

- Sit up if possible. This can help move the stool down in the intestine. If you cannot sit up, lie on your side.

It is important to be clean and gentle when inserting anything into the anus.

- Always wash your hands and use gloves. Lubricate the finger of the glove with K-Y jelly or a similar product.

- For digital stimulation, gently insert the finger in the anus and move it in a circular motion for no more than 10 to 20 seconds every 5 to 10 minutes until you have a bowel movement.

- To remove stool, gently insert the finger and remove stool. Continue to do so until none comes out. Wait a few minutes and then try again to see if any more stool has moved down.

- To insert a suppository, first remove stool. Otherwise, the suppository won’t work. Take the wrapper off the suppository and insert it as high in your rectum as you can.

Note: Bowel problems can trigger autonomic dysreflexia, which causes sudden very high blood pressure and headaches. If not treated promptly and correctly, it may lead to seizures, stroke, and even death. These complications are rare, but it is important to know the symptoms and watch for them.

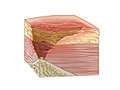

Pressure Injuries

When you have a spinal cord injury, the nerves that normally signal discomfort and alert you to relieve pressure by changing position may no longer work. This can cause pressure injuries, which are injuries to the skin and the tissue under the skin. They often develop on skin that covers bony areas, such as the hips, heels, or tailbone. Pressure injuries can also occur in places where the skin folds over on itself. They are described in four stages that range from mild reddening of the skin to severe complications, such as infection of the bone or blood. They can be hard to treat and slow to heal.

Pressure injuries may be caused by:

- Constant pressure on the skin, which reduces blood supply to the skin and to the tissues under the skin.

- Friction, which is the rubbing that occurs when a person is pulled across bed sheets or other surfaces.

- Shear, which is movement (such as sliding down a chair) that causes the skin to fold over itself, cutting off the blood supply.

- Irritation of the skin from things such as sweat, urine, or feces.

Pressure injuries are usually diagnosed with a physical exam. A skin and wound culture or a skin biopsy may be done if your doctor thinks you may have an infection.

Preventing pressure injuries

You or your caregiver can help prevent pressure injuries. These steps can help keep skin healthy:

- Prevent constant pressure on any part of the body.

- Change positions and turn often to help reduce constant pressure on the skin. Learn the proper way to move yourself or to move a person you are caring for so that you avoid folding and twisting skin layers.

- Spread body weight. Use pressure-relieving supports and devices, especially if you are confined to a bed or chair for any length of time, to help prevent pressure injuries. Pad the metal parts of a wheelchair to help reduce pressure and friction.

- Avoid sliding, slipping, or slumping, or being in positions that put pressure directly on an existing pressure injury. Try to keep the head of a bed, a recliner chair, or a reclining wheelchair raised no more than 30 degrees.

- Eat a balanced diet that includes plenty of protein.

- Keep the skin clean and free of body fluids or feces.

- Use skin lotions to keep the skin from drying out and cracking, which makes the skin more likely to get pressure injuries. Barrier lotions or creams have ingredients that can act as a shield to help protect the skin from moisture or irritation.

For more information on prevention, see the topic Pressure Injuries: Prevention and Treatment.

Signs to look for

Watch for early signs of a pressure injury. These can include:

- A new area of redness that doesn’t go away within a few minutes of taking pressure off the area.

- An area of skin that is warmer or cooler than the surrounding skin.

- An area of skin that is firmer or softer than the skin around it.

Contact your doctor if you:

- Think a pressure injury is starting and you aren’t able to adjust your activities and positioning to protect the area.

- Notice an increase in the size or drainage of the sore.

- Notice increased redness around the sore or black areas starting to form.

- Notice that the sore begins to smell bad and/or the drainage becomes a greenish color.

- Have a fever.

Treating pressure injuries

General treatment for pressure injuries is to keep the area dry and clean, eat well, and reduce pressure. All pressure injuries need to be treated early. If a sore progresses to stage 3 or 4, it is hard to treat and can lead to serious complications. Specific treatment depends on the stage of the pressure injury.

For more information on treatment, see the topic Pressure Injuries: Prevention and Treatment.

Note: Pressure injuries can trigger autonomic dysreflexia, which causes sudden very high blood pressure and headaches. If not treated promptly and correctly, it may lead to seizures, stroke, and even death. These complications are rare, but it is important to know the symptoms and watch for them.

Lung Care

Breathing is usually something we do without thinking. But a spinal cord injury (SCI) may affect some of the muscles needed for breathing. This makes it hard to breathe, cough, and bring up mucus from the lungs, which leads to a greater risk of lung infections such as pneumonia.

How your breathing muscles are affected and what it means to your ability to breathe depends on which part of your spine was injured.

- People with injuries lower on the spinal cord (below T12) usually don’t lose control of these muscles and have no trouble breathing.

- People with SCIs high on the neck may need a ventilator. People with injuries between these levels have a partial loss of the breathing muscles but can usually still breathe on their own.

Preventing lung problems

There are things you can do to help prevent lung problems.

- Know the symptoms of pneumonia. If you have the symptoms, contact your doctor immediately. Talk to him or her about getting vaccinated for pneumonia and influenza. For more information, see the topic Pneumonia.

- Practice coughing. A forceful cough is important, because it will help you bring up mucus in the lungs, which can help prevent some lung complications. If your cough is weak and you have trouble bringing up mucus, you may need an assisted cough.

- Remove excess mucus from the lungs. Coughing may not bring up all the mucus. In this case, you may need chest physiotherapy and/or postural drainage.

- Practice breathing. Doing exercises, such as breathing out forcefully, can help strengthen the muscles you use for breathing.

- Don’t smoke.

And there are things you can do that aren’t directly related to your lungs.

- Sit up straight, and move around as much as possible. This helps prevent mucus buildup.

- Eat a healthy diet. Eating healthy foods will help keep you from gaining or losing weight. Being either overweight or underweight can lead to lung problems.

- Drink plenty of fluids, preferably water. This helps prevent the mucus in your lungs from getting thick, and it makes the mucus easier to cough up. If you have concerns with bladder control, talk to your doctor about how much and when to drink fluids.

Choking: What to do

Choking is a danger if you have an SCI, because the usual cough mechanism may not be strong enough to bring up the item that is choking you. If choking occurs, your caregiver should:

- Hit you sharply 4 times between the shoulder blades with the palm of the hand.

- Use an assisted cough 4 times.

- Repeat steps 1 and 2 above until you stop choking.

Intimacy and Fertility

All spinal cord injuries are different. How they affect intimacy and sexual function—and how people will react to the change—varies. Because of this, you need to make your own observations and evaluate your experiences to understand your changes in sexual function and how to best deal with them.

After a spinal cord injury (SCI), how you look and what you are able to do changes. An SCI may also affect how your sexual organs work. These changes often result in frustration, anger, and disappointment, all of which can strain a relationship. People with SCIs may wonder if they will be able to maintain the relationship they are in or develop new ones.

But being intimate means more than just having sex. Your interests, ideas, and behavior play a greater role in defining you than your appearance or your ability to have sex. A relationship depends on many things, including shared interests, how you deal with personal likes and dislikes, and how you treat each other.

The most important thing in a relationship is how well you communicate. Talk to your partner. Be honest about how the SCI has affected your sexual function and how you feel about it. Always keep in mind that people with SCIs can have relationships and marry, have an active sex life, and have children.

Desire and sexual arousal

Usually, men and women are sexually aroused through two pathways: direct stimulation of the genitals or other erotic area or through thinking, hearing, or seeing something sexually arousing. In men, this usually causes an erection, and in women it causes lubrication of the vagina and swelling of the clitoris. An SCI can affect either of these pathways and may change a person’s physical response to arousal. Most people remain interested in sexual activity after an SCI, although the level of interest may decrease.

Many men with an SCI resume sexual activity within about 1 year of the injury. Men who are able to have an erection may find that the erection isn’t rigid enough or doesn’t last long enough for sexual activity. Some have retrograde ejaculation, in which semen goes into the bladder instead of out through the penis.

Women may have some, or complete, loss of vaginal sensation and muscle control. Both men and women can achieve orgasm, although it may not be as intense as before the SCI.

Your sex life will probably be different after your spinal cord injury, but sexual intimacy is still possible and encouraged. Your rehabilitation center may have a counselor or other health professional who specializes in sexual health after an SCI. He or she may be able to help you and your partner with these issues.

Treating sexual problems

Always talk to a doctor familiar with SCIs before using any medicines or devices. Discuss the location of your injury, possible side effects, and any other medical conditions you have.

You also need to watch for autonomic dysreflexia, which causes sudden very high blood pressure. If not treated promptly and correctly, it may lead to seizures, stroke, and even death. These complications are rare, but it is important to know the symptoms and watch for them.

Men who can’t get an erection can use the treatments for erection problems (erectile dysfunction). These include:

- Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE-5 inhibitors) such as sildenafil (Viagra), vardenafil (Levitra), and tadalafil (Cialis). But PDE-5 inhibitors can be dangerous for certain men.

- Medicines you inject into the penis, such as alprostadil (Caverject) and papaverine (Pavabid).

- Medicine you insert into the penis, such as alprostadil (prostaglandin E1).

- Vacuum devices, which help blood flow into the penis.

- Penile implants, which are rigid or semirigid cylinders implanted into the penis.

- Vibrators made for men.

For information on the treatment of erection problems, see the topic Erection Problems.

Women who have problems being aroused and have little or no vaginal lubrication may use:

- Sildenafil (Viagra), a medicine used to treat erectile dysfunction in men. It can also help women become aroused.

- A vibrator.

- A water-based lubricant, such as Astroglide or K-Y Jelly. Do not use oil-based lubricants.

Both men and women can use sensual exercises that you do with your partner to find areas of your body that react to stimulation.

Fertility in men

Most men with SCIs have poor sperm quality and have trouble ejaculating. To have children, men with SCIs can use penile stimulation to obtain sperm for assistive reproductive technologies. Vibrators are available that are specially made to induce ejaculation in men with SCIs.

Vibrators can damage your skin. Use them carefully if you don’t have feeling in your penis.

If vibrator stimulation isn’t successful, rectal probe electroejaculation (RPE) is an option. In this procedure, your doctor inserts an electrical probe into the rectum to stimulate ejaculation.

Fertility in women

An SCI usually won’t affect a woman’s ability to get pregnant. You may have a brief pause in your menstrual cycle after an SCI. But after your period returns, you will probably be able to get pregnant.

If you are sexually active after your injury, make sure to use birth control if you don’t want to get pregnant.

If you do want to get pregnant, make sure to be aware of the special medical, psychological, and social issues involved in an SCI pregnancy. Work with doctors who understand these issues. Common concerns and complications during pregnancy include:footnote 1

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs), which increase during pregnancy in women with SCIs. Your urine should be tested frequently.

- Pressure injuries. The extra weight of pregnancy puts greater pressure on the skin and may increase the risk of pressure injuries. Be sure you perform skin exams regularly.

- Mobility devices. The weight gain of pregnancy may mean that you need to change the type of mobility device you use. You may also have to change your transfer technique.

- Lung function. Women with damage higher on the spinal cord may have reduced lung function. Ventilator support may be needed.

- Autonomic dysreflexia. During labor, the symptoms of this condition may be the same as those seen in uterine contractions. Anesthesia should be used during labor to prevent this serious condition.

Life With a Spinal Cord Injury

Grieving

Grief is one of the many challenges of adjusting to life after a spinal cord injury. It’s your reaction to loss, and it affects you both emotionally and physically. But letting your emotions control you can result in unhealthy decisions and behavior, a longer rehab, and taking longer to adjust to your spinal cord injury (SCI). Feeling and naming your emotions, and talking to others about them, will help you feel more solid and in control.

Talking to a professional counselor who understands the challenges of living with an SCI can be very helpful during tough times.

For more information on the grieving process, see the topic Grief and Grieving.

Chronic pain

Pain in an SCI can be complicated and confusing. You may feel pain where you have feeling. But you may also feel pain in an area where otherwise you have no feeling. The pain may be severe at some times. But at other times it may disappear or bother you only a little.

The most common type of pain is neuropathic pain, caused by damage to the nervous system. Other types of pain include musculoskeletal pain (in the bones, muscles, and joints), and visceral pain (in the abdomen).

Don’t ignore your pain. Talk to your doctor about it. He or she can help figure out the type of pain and how to manage it. Also, pain can signal a more serious problem.

The best treatment depends on the type of pain. But you will probably need to:

- Use medicines and other treatments, such as acupuncture.

- Modify your activities and activity levels.

For more information on managing pain, see the topic Chronic Pain.

Strength and flexibility

Movement is what keeps your muscles strong and your joints flexible. So if you cannot move your muscles and joints easily, you may lose strength and some of your range of motion. This will make it harder to perform daily activities, such as getting dressed or moving between your wheelchair and other locations. With exercise, you can keep or improve your flexibility and reduce muscle spasticity. Exercise can also help prevent heart problems, diabetes, pressure injuries, pneumonia, high blood pressure, urinary tract infections, and weight problems.

What exercises you can do will depend on what part of your spinal cord was injured. You may be able to do:

- Flexibility exercises on your own or with help.

- Strength exercises with free weights or weight machines.

Taking part in sports is an excellent way to exercise. And there are often leagues or groups to promote wheelchair basketball and racing and other activities. Staying active provides both physical and emotional benefits.

Note: Exercise may trigger autonomic dysreflexia, which can cause sudden very high blood pressure and headaches. If not treated promptly and correctly, it may lead to seizures, stroke, and even death. These complications are rare, but it is important to know the symptoms and watch for them.

Nutrition

Eating a healthy diet can help you reduce your risk of some complications and can make other tasks, such as bowel management, easier. And it can help you reach and stay at a healthy weight. Being either underweight or overweight increases your risk of pressure injuries.

If you have special nutritional needs, such as needing extra protein or fiber, a registered dietitian can help you plan a diet.

For more information on a healthy diet and weight, see:

Mobility

Mobility is an important aspect of a spinal cord injury. Mobility devices, such as crutches, walkers, wheelchairs, and scooters, can help you be more independent. They may allow you to work, shop, travel, or take part in sports.

Moving from a wheelchair to another location is known as a transfer. Your injury and strength will determine what type of transfer you can do. You may be able to do it yourself, or you may need help. There are some important things to know for safe transfers, such as to lock your wheelchair and make the distance between the transfer surfaces as small as possible.

Adapting your home

As your rehab ends, you and your loved ones need to start thinking about what you need to do when you are at home. Because you may have to use a wheelchair (lowering your height) and have limited movement and feeling, you may have to adapt your home.

Considerations for adapting your home include ramps and widened doorways, special utensils for eating, and special devices for dressing and grooming.

Thinking of the future

Today, with improved medical care and support, the outlook for people with SCIs is better than ever. In many cases, 1 year after the injury, life expectancy is close to that of a person without an SCI.footnote 2

If you are planning to work, you have the same legal rights as before your injury. People with spinal cord injuries who want to work are legally protected from discrimination by the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Plan ahead for possible serious and life-threatening complications. You, your family, and your doctor should discuss what types of medical treatment you want if you have a sudden, life-threatening problem. You may want to create an advance directive to state your wishes if you become unable to communicate.

For more information, see:

When to Call a Doctor

There may be a time when you have a medical emergency and need to contact a doctor.

Be prepared to call your spinal care injury provider, 911, or other emergency services if you or the person with the spinal cord injury has the symptoms of autonomic dysreflexia, which causes sudden very high blood pressure. If it isn’t treated promptly and correctly, it may lead to seizures, stroke, and even death. Symptoms include:

- A pounding headache.

- A flushed face and/or red blotches on the skin above the level of spinal injury.

- Sweating above the level of spinal injury.

- Nasal stuffiness.

- Nausea.

- A slow heart rate (bradycardia).

- Goose bumps below the level of spinal injury.

- Cold, clammy skin below the level of spinal injury.

Call 911 or other emergency services if you fall or have another accident and you notice:

- Swelling on a part of your body where you have no feeling or movement.

- Increased muscle spasms or other signs of spasticity.

Call your doctor right away if you have symptoms of a urinary tract infection. These include:

- Fever and chills.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Headache.

- Reddish or pinkish urine.

- Foul-smelling urine.

- Cloudy urine.

- Increased muscle spasms or other signs of spasticity.

Depending on your level of injury, you may also feel burning while urinating and/or pain or discomfort in the lower pelvic area, belly, or lower back.

Call your doctor right away if you have symptoms of pneumonia. These include:

- Fever of 100.4°F (38°C) to 106°F (41.1°C).

- Shaking chills.

- Cough that often produces colored mucus from the lungs. Mucus may be rust-colored or green or tinged with blood. Older adults may have only a slight cough and no mucus.

- Rapid, often shallow, breathing.

- Chest wall pain, often made worse by coughing or deep breathing.

- Fatigue and feelings of weakness (malaise).

- Increased muscle spasms or other signs of spasticity.

Call your doctor for an appointment if you have a pressure injury and:

- The skin is broken.

- The sore has increased in size or is draining more.

- It has increased in redness, or black areas are starting to form.

- It starts to smell bad, or the drainage becomes a greenish color.

- You have a fever.

Concerns of the Caregiver

Your first experience as a caregiver for a spinal cord injury (SCI) usually comes during rehabilitation (rehab). Although the rehab team takes the lead at this point in your loved one’s recovery, there are some things you can do to help.

- Visit and talk with your loved one often. Find activities you can do together, such as playing cards or watching TV. Try to keep in touch with your loved one’s friends as much as possible. Encourage them to visit.

- Help your loved one practice and learn new skills.

- Find out what he or she can do independently or needs help with. Avoid doing things for your loved one that he or she is able to do without your help.

- Learn what you and your family can do after your loved one returns home. This may include helping him or her with the wheelchair, getting to and from the bathroom, and eating.

After rehab

Before your loved one returns home, a decision has to be made about who is to be the main caregiver. You or another family member may feel that you should be the main caregiver. But there may be reasons why this could be hard, such as:

- Your own health, which may limit what you can do to help.

- Your job, which provides all the income for your family and leaves you with limited time.

- Your own doubts that you could handle taking care of someone who has an SCI.

Discuss with the rehab team what it means to be a caregiver. They can help you see what the full impact of caring for someone with an SCI will be. And if you cannot be a full-time caregiver, the rehab team can help you find a nursing home, an assisted-living facility, or in-home help. They can also give you training in helping your loved one, even if you aren’t the full-time caregiver. You may need to help him or her do exercises, move in and out of the wheelchair, and get dressed, for example.

Your needs

Whether or not you are the main caregiver, you need to attend to your own well-being.

- Don’t try to do everything yourself. Ask other family members to help. And find out what other type of help may be available.

- Take care of yourself by eating well and getting enough rest.

- Make sure you don’t ignore your own health while you are caring for your loved one. Keep up with your own doctor visits, and make sure to take your medicines regularly, if needed.

- Find a support group to attend. Support groups may be able to offer advice about insurance coverage too.

- Schedule time for yourself. Get out of the house to do things you enjoy, run errands, or go shopping.

Communicate

Whether or not you are the main caregiver for your loved one, living with and/or caring for him or her can be both rewarding and difficult. Watching someone deal with such a serious injury can be painful but also inspirational. Sharing the small and large victories can provide a shared pleasure and forge a stronger relationship. But setbacks and “bad days” can be frustrating and traumatic.

The key to working through frustrations is communication. It is important that both you and your loved one talk about what bothers you and about what your expectations are. In a sense, you are in a new relationship: roles in your family may have changed dramatically. Discuss what you are feeling about the changes, and explain them. This can help you understand each other’s needs and foster a healthy relationship. Love and support are key to your loved one’s recovery and to your well-being as a caregiver.

The Search for a Cure

In the past, the results of a spinal cord injury were considered permanent, but new research is changing this outlook. There may be a cure for paralysis some day.

Major research areas for SCIs include ways to stimulate activity in damaged nerve cells (neurorestorative), stimulate growth in damaged nerve cells (neuroregenerative), transplant new nerve tissue into the spinal cord (neuroconstructive), and insert genes into the spinal cord (neurogenetic). Research is also looking at ways to improve what people with SCIs can do physically (functional research).

Spinal cord injuries are extremely complex. And research must move from theory to practical and from animal studies to human studies. When a treatment is being studied in humans, it must be proved beneficial and safe. And it can take years before a new treatment reaches the public.

References

Citations

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2002, reaffirmed 2005). Obstetric management of patients with spinal cord injuries. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 275. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 100(3): 625–627.

- National SCI Statistical Center (2012). Spinal cord injury facts and figures at a glance. Birmingham, AL: National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Available online: https://www.nscisc.uab.edu.

Other Works Consulted

- Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine (2006). Bladder management for adults with spinal cord injury. Available online: http://www.pva.org.

- Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine (2008). Early acute management in adults with spinal cord injury: A clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 31(4): 403–479. Accessed August 1, 2018.

- Keenan MAE, et al. (2014). Rehabilitation. In HB Skinner, PJ McMahon, eds., Current Diagnosis and Treatment in Orthopedics, 5th ed., pp. 595–642. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- McDonald JW, Becker D (2003). Spinal cord injury: Promising interventions and realistic goals. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 82(10, Suppl): S38–S49.

Current as of: March 28, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:Adam Husney, MD – Family Medicine & Martin J. Gabica, MD – Family Medicine & E. Gregory Thompson, MD – Internal Medicine & Kathleen Romito, MD – Family Medicine & Nancy E. Greenwald, MD – Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

<span class=”

<span class=”