Presbyopia

Topic Overview

What is presbyopia?

Presbyopia is the normal worsening of vision with age, especially near vision. As you approach middle age, the lenses in your eyes begin to thicken and lose their flexibility. The ability of the lens to bend allows our eyes to focus on objects at varying distances (accommodation). The loss of this ability means that vision gets worse and objects cannot be brought into focus. This typically becomes noticeable some time around age 40 when you realize that you have to hold a book or newspaper farther from your face to focus on it.

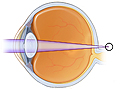

Normally, a muscle surrounding the lens in your eye expands or contracts, depending on the distance to the object you’re focusing on. With presbyopia, the muscle still works, but it may not work as well. Also, the lens loses much of its flexibility and won’t bend enough to bring close objects into focus. Images are then focused behind the retina instead of directly on it, leaving close vision blurred. Putting greater distance between the object and your eye brings the object into focus. For example, holding a newspaper farther from your face helps you see the words. For this reason, presbyopia is sometimes called “long-arm syndrome.”

What causes presbyopia?

Presbyopia is a natural part of aging. As you grow older, the lenses in your eyes thicken. They lose their elasticity, and the muscles surrounding the lenses weaken. Both these changes decrease your ability to focus, especially on near objects. The changes take place gradually, though it may seem that this loss of accommodation occurs quickly.

What are the symptoms?

The main symptom of presbyopia is blurred vision, especially when you do close work or try to focus on near objects. This is worse in dim light or when you are fatigued. Presbyopia can also cause headaches or eyestrain.

How is presbyopia diagnosed?

Presbyopia can usually be diagnosed with a general eye exam. Your doctor will probably test your visual acuity (sharpness of vision), your refractive power (the ability of your eyes to change focus from near to far), the condition of the muscles in your eye, and the condition of your retina. He or she will probably also take measurements for glasses or contact lenses at the time of the exam.

How is it treated?

Presbyopia can usually be corrected with glasses or contact lenses. If you didn’t need glasses or contacts before presbyopia appeared, you can probably correct your eyesight by using reading glasses for close work. Glasses you buy without a prescription may be sufficient. But check with your eye doctor to find out the right glasses for you. If you do buy glasses without a prescription, try out a few different pairs of varying strength (magnification) to make sure you get glasses that will help you read without straining.

If you already use glasses or contacts to correct nearsightedness, farsightedness, or astigmatism, you’ll need a new prescription that will also correct presbyopia. You may wish to use bifocals, in which distant vision is corrected at eye level and close vision is corrected at the bottom. Other options include trifocal glasses, which can correct for distant, near, and middle vision; progressive lenses, which give a smooth transition between distant, middle, and near vision; bifocal contact lenses; or monovision contact lenses, which correct distant vision in your dominant eye and close vision in your weaker eye. Your prescription may have to be changed over time as presbyopia gets worse.

If you don’t want to wear glasses or contacts, surgery may be an option. Procedures that can help treat presbyopia include laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) and photorefractive keratectomy (PRK). Both of these surgeries use lasers to reshape the cornea of your eye. Laser surgery cannot give you both distance and near vision in the same eye. But your doctor can correct one eye for distance vision and the other eye for near vision.

Another surgery option is clear lens extraction with an intraocular lens implant, in which the natural lens is removed and an artificial one is implanted to replace it. Some lens implants correct either distance or near vision. Others (called multifocal implants) correct both near and distance vision.

None of these surgeries will restore perfect vision—you will have to compromise. For example, you may have surgery to correct distance vision and then use reading glasses for near vision. Or you may have one eye adjusted for near vision and one for distance vision, which would reduce your depth perception. New procedures that reverse presbyopia are being developed and tested.

Will your vision continue to get worse?

Near vision begins to decline due to presbyopia at around age 40. Your eyes continue to lose the ability to accommodate—requiring changes to prescriptions for glasses or contacts—until you reach your early 60s. Then accommodation stabilizes. But it’s important to get routine eye exams to check for other problems that can affect your vision, such as glaucoma or macular degeneration.

References

Other Works Consulted

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (2017). Refractive Errors and Refractive Surgery (Preferred Practice Pattern). San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology. https://www.aao.org/ppp. Accessed July 20, 2018.

- Riordan-Eva P (2011). Optics and refraction. In P Riordan-Eva, ET Cunningham, eds., Vaughan and Asbury’s General Ophthalmology, 18th ed., pp. 396–411. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Trobe JD (2006). Principal ophthalmic conditions. Physician’s Guide to Eye Care, 3rd ed., pp. 93–140. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology.

Current as of: May 5, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:Kathleen Romito, MD – Family Medicine & Adam Husney, MD – Family Medicine & E. Gregory Thompson, MD – Internal Medicine & Christopher Joseph Rudnisky, MD, MPH, FRCSC – Ophthalmology

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.