Heart Attack and Unstable Angina

Topic Overview

What is a heart attack?

A heart attack occurs when blood flow to the heart is blocked. Without blood and the oxygen it carries, part of the heart starts to die. A heart attack doesn’t have to be deadly. Quick treatment can restore blood flow to the heart and save your life.

Your doctor might call a heart attack a myocardial infarction, or MI. Your doctor might also use the term acute coronary syndrome for your heart attack or unstable angina.

What is angina, and why is unstable angina a concern?

Angina (say “ANN-juh-nuh” or “ann-JY-nuh”) is a symptom of coronary artery disease. Angina occurs when there is not enough blood flow to the heart. Angina can be dangerous. So it is important to pay attention to your symptoms, know what is typical for you, learn how to control it, and know when to call for help.

Symptoms of angina include chest pain or pressure, or a strange feeling in the chest. Some people feel pain, pressure, or a strange feeling in the back, neck, jaw, or upper belly, or in one or both shoulders or arms.

There are two types of angina:

- Stable angina means that you can usually predict when your symptoms will happen. You probably know what things cause your angina. For example, you know how much activity usually causes your angina. You also know how to relieve your symptoms with rest or nitroglycerin.

- Unstable angina means that your symptoms have changed from your typical pattern of stable angina. Your symptoms do not happen at a predictable time. For example, you may feel angina when you are resting. Your symptoms may not go away with rest or nitroglycerin.

Unstable angina is an emergency. It may mean that you are having a heart attack.

What causes a heart attack?

Heart attacks happen when blood flow to the heart is blocked. This usually occurs because fatty deposits called plaque have built up inside the coronary arteries, which supply blood to the heart. If a plaque breaks open, the body tries to fix it by forming a clot around it. The clot can block the artery, preventing the flow of blood and oxygen to the heart.

This process of plaque buildup in the coronary arteries is called coronary artery disease, or CAD. In many people, plaque begins to form in childhood and gradually builds up over a lifetime. Plaque deposits may limit blood flow to the heart and cause angina. But too often, a heart attack is the first sign of CAD.

Things like intense exercise, sudden strong emotion, or illegal drug use (such as a stimulant, like cocaine) can trigger a heart attack. But in many cases, there is no clear reason why heart attacks occur when they do.

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms of a heart attack include:

- Chest pain or pressure, or a strange feeling in the chest.

- Sweating.

- Shortness of breath.

- Nausea or vomiting.

- Pain, pressure, or a strange feeling in the back, neck, jaw, or upper belly, or in one or both shoulders or arms.

- Lightheadedness or sudden weakness.

- A fast or irregular heartbeat.

For men and women, the most common symptom is chest pain or pressure. But women are somewhat more likely than men to have other symptoms like shortness of breath, nausea, and back or jaw pain.

Here are some other ways to describe the pain from heart attack:

- Many people describe the pain as discomfort, pressure, squeezing, or heaviness in the chest.

- People often put their fist to their chest when they describe the pain.

- The pain may spread down the left shoulder and arm and to other areas, such as the back, jaw, neck, or right arm.

Unstable angina has symptoms similar to a heart attack.

What should you do if you think you are having a heart attack?

If you have symptoms of a heart attack, act fast. Quick treatment could save your life.

If your doctor has prescribed nitroglycerin for angina:

- Take 1 dose of nitroglycerin and wait 5 minutes.

- If your symptoms don’t improve or if they get worse,call 911 or other emergency services. Describe your symptoms, and say that you could be having a heart attack.

- Stay on the phone. The emergency operator will tell you what to do. The operator may tell you to chew 1 adult-strength or 2 to 4 low-dose aspirin. Aspirin helps keep blood from clotting, so it may help you survive a heart attack.

- Wait for an ambulance. Do not try to drive yourself.

If you do not have nitroglycerin:

- Call 911 or other emergency services now. Describe your symptoms, and say that you could be having a heart attack.

- Stay on the phone. The emergency operator will tell you what to do. The operator may tell you to chew 1 adult-strength or 2 to 4 low-dose aspirin. Aspirin helps keep blood from clotting, so it may help you survive a heart attack.

- Wait for an ambulance. Do not try to drive yourself.

The best choice is to go to the hospital in an ambulance. The paramedics can begin lifesaving treatments even before you arrive at the hospital. If you cannot reach emergency services, have someone drive you to the hospital right away. Do not drive yourself unless you have absolutely no other choice.

How is a heart attack treated?

If you go to the hospital in an ambulance, treatment will be started right away to restore blood flow and limit damage to the heart. You may be given:

- Aspirin and other medicines to prevent blood clots.

- Medicines that break up blood clots (thrombolytics).

- Medicines to decrease the heart’s workload and ease pain.

At the hospital, you will have tests, such as:

- Electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG). It can detect signs of poor blood flow, heart muscle damage, abnormal heartbeats, and other heart problems.

- Blood tests, including tests to see whether cardiac enzymes are high. Having these enzymes in the blood is usually a sign that the heart has been damaged.

- Cardiac catheterization, if the other tests show that you may be having a heart attack. This test shows which arteries are blocked and how your heart is working.

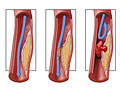

If cardiac catheterization shows that an artery is blocked, a doctor may do angioplasty right away to help blood flow through the artery. Or a doctor may do emergency bypass surgery to redirect blood around the blocked artery.

After these treatments, you will take medicines to help prevent another heart attack. Take all of your medicines correctly. Do not stop taking your medicine unless your doctor tells you to. If you stop taking your medicine, you might raise your risk of having another heart attack.

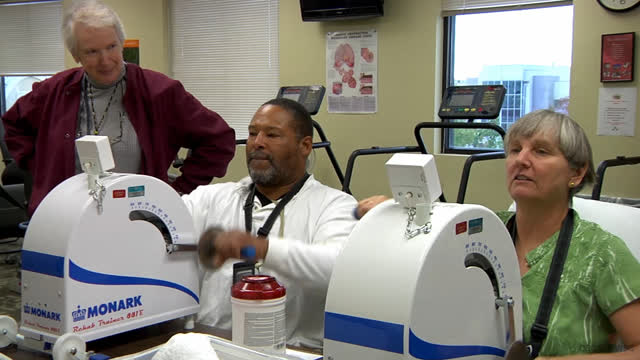

After you have had a heart attack, the chance that you will have another one is higher. Taking part in a cardiac rehab program helps lower this risk. A cardiac rehab program is designed for you and supervised by doctors and other specialists. It can help you learn how to eat a balanced diet and exercise safely.

It is common to feel worried and afraid after a heart attack. But if you are feeling very sad or hopeless, ask your doctor about treatment. Getting treatment for depression may help you recover from a heart attack.

Can you prevent a heart attack?

Heart attacks are usually the result of heart disease, so taking steps to delay or reverse coronary artery disease can help prevent a heart attack. Heart disease is a leading cause of death for both men and women, so these steps are important for everyone.

To improve your heart health:

- Don’t smoke, and avoid secondhand smoke. Quitting smoking can quickly reduce the risk of another heart attack or death.

- Eat a heart-healthy diet that includes plenty of fish, fruits, vegetables, beans, high-fiber grains and breads, and olive oil.

- Get regular exercise. Your doctor can suggest a safe level of exercise for you.

- Stay at a healthy weight. Lose weight if you need to.

- Manage other health problems such as diabetes, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure.

- Lower your stress level. Stress can damage your heart.

- If you have talked about it with your doctor, take a low-dose aspirin every day. But taking aspirin isn’t right for everyone, because it can cause serious bleeding.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Cause

A heart attack or unstable angina is caused by sudden narrowing or blockage of a coronary artery. This blockage keeps blood and oxygen from getting to the heart.

This blockage happens because of a problem called atherosclerosis, or hardening of the arteries. This is a process where fatty deposits called plaque build up inside arteries. Arteries are the blood vessels that carry oxygen-rich blood throughout your body. When atherosclerosis happens in the coronary arteries, it leads to heart disease.

If the plaque breaks apart, it can cause a heart attack or unstable angina. A tear or rupture in the plaque tells the body to repair the injured artery lining, much as the body might heal a cut on the skin. A blood clot forms to seal the area. The blood clot can completely block blood flow to the heart muscle.

With a heart attack, lack of blood flow causes the heart’s muscle cells to start to die. With unstable angina, the blood flow is not completely blocked by the blood clot. But the blood clot can quickly grow and block the artery.

A stent in a coronary artery can also become blocked and cause a heart attack. The stent might become narrow again if scar tissue grows after the stent is placed. And a blood clot could get stuck in the stent and block blood flow to the heart.

Heart attack triggers

In most cases, there are no clear reasons why heart attacks occur when they do. But sometimes your body releases adrenaline and other hormones into the bloodstream in response to intense emotions such as anger, fear, and the “fight or flight” impulse. Heavy physical exercise, emotional stress, lack of sleep, and overeating can also trigger this response. Adrenaline increases blood pressure and heart rate and can cause coronary arteries to constrict, which may cause an unstable plaque to rupture.

Rare causes

In rare cases, the coronary artery spasms and contracts, causing heart attack symptoms. If severe, the spasm can completely block blood flow and cause a heart attack. Most of the time in these cases, atherosclerosis is also involved, although sometimes the arteries are not narrowed. The spasms can be caused by smoking, cocaine use, cold weather, an electrolyte imbalance, and other things. But in many cases, it is not known what triggers the spasm.

Another rare cause of heart attack can be a sudden tear in the coronary artery, or spontaneous coronary artery dissection. In this case, the coronary artery tears without a known cause.

Symptoms

Heart attack

Symptoms of a heart attack include:

- Chest pain or pressure, or a strange feeling in the chest.

- Sweating.

- Shortness of breath.

- Nausea or vomiting.

- Pain, pressure, or a strange feeling in the back, neck, jaw, or upper belly, or in one or both shoulders or arms.

- Lightheadedness or sudden weakness.

- A fast or irregular heartbeat.

Call 911 or other emergency services immediately if you think you are having a heart attack.

Nitroglycerin. If you typically use nitroglycerin to relieve angina and if one dose of nitroglycerin has not relieved your symptoms within 5 minutes, call 911. Do not wait to call for help.

Unstable angina

Unstable angina symptoms are similar to a heart attack.

Call 911 or other emergency services immediately if you think you are having a heart attack or unstable angina.

People who have unstable angina often describe their symptoms as:

- Different from their typical pattern of stable angina. Their symptoms do not happen at a predictable time.

- Suddenly becoming more frequent, severe, or longer-lasting or being brought on by less exertion than before.

- Occurring at rest with no obvious exertion or stress. Some say these symptoms may wake you up.

- Not responding to rest or nitroglycerin.

Women’s symptoms

For men and women, the most common symptom is chest pain or pressure. But women are somewhat more likely than men to have other symptoms like shortness of breath, nausea, and back or jaw pain.

Women are more likely than men to delay seeking help for a possible heart attack. Women delay for many reasons, like not being sure it is a heart attack or not wanting to bother others. But it is better to be safe than sorry. If you have symptoms of a possible heart attack, call for help. When you get to the hospital, don’t be afraid to speak up for what you need. To get the tests and care that you need, be sure your doctors know that you think you might be having a heart attack.

For more information, see Heart Disease and Stroke in Women: Reducing Your Risk.

Other ways to describe chest pain

People who are having a heart attack often describe their chest pain in various ways. The pain:

- May feel like pressure, heaviness, weight, tightness, squeezing, discomfort, burning, a sharp ache (less common), or a dull ache. People often put a fist to the chest when describing the pain.

- May radiate from the chest down the left shoulder and arm (the most common site) and also to other areas, including the left shoulder, middle of the back, upper portion of the abdomen, right arm, neck, and jaw.

- May be diffuse—the exact location of the pain is usually difficult to point out.

- Is not made worse by taking a deep breath or pressing on the chest.

- Usually begins at a low level, then gradually increases over several minutes to a peak. The discomfort may come and go. Chest pain that reaches its maximum intensity within seconds may represent another serious problem, such as an aortic dissection.

It is possible to have a “silent heart attack” without any symptoms, but this is rare.

What Increases Your Risk

Things that increase your risk of a heart attack are the things that lead to a problem called atherosclerosis, or hardening of the arteries. Atherosclerosis is the starting point for heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, heart attack, and stroke.

Your doctor can help you find out your risk of having a heart attack. Knowing your risk is just the beginning for you and your doctor. Knowing your risk can help you and your doctor talk about whether you need to lower your risk. Together, you can decide what treatment is best for you.

Things that increase your risk of a heart attack include:

- High cholesterol.

- High blood pressure.

- Diabetes.

- Smoking.

- A family history of early heart disease. Early heart disease means you have a male family member who was diagnosed before age 55 or a female family member who was diagnosed before age 65.

Your age, sex, and race can also raise your risk. For example, your risk increases as you get older.

Women and heart disease

Women have unique risk factors for heart disease, including hormone therapy and pregnancy-related problems. These things can raise a woman’s risk for a heart attack or stroke.

See the topic Heart Disease and Stroke in Women: Reducing Your Risk for more information on risk, symptoms, and prevention of heart disease and stroke.

NSAIDs

Most nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which are used to relieve pain and fever and reduce swelling and inflammation, may increase the risk of heart attack. This risk is greater if you take NSAIDs at higher doses or for long periods of time. People who are older than 65 or who have existing heart, stomach, or intestinal disease are more likely to have problems. Be safe with medicines. Read and follow all instructions on the label.

Aspirin, unlike other NSAIDs, can help certain people lower their risk of a heart attack or stroke. But taking aspirin isn’t right for everyone, because it can cause serious bleeding. Talk to your doctor before you start taking aspirin every day.

Regular use of other NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, may make aspirin less effective in preventing heart attack and stroke.

For information on how to prevent a heart attack, see the Prevention section of this topic.

When to Call a Doctor

Do not wait if you think you are having a heart attack. Getting help fast can save your life. Even if you’re not sure it’s a heart attack, have it checked out.

Call 911 or other emergency services immediately if you have symptoms of a heart attack. These may include:

- Chest pain or pressure, or a strange feeling in the chest.

- Sweating.

- Shortness of breath.

- Nausea or vomiting.

- Pain, pressure, or a strange feeling in the back, neck, jaw, or upper belly, or in one or both shoulders or arms.

- Lightheadedness or sudden weakness.

- A fast or irregular heartbeat.

After you call 911, the operator may tell you to chew 1 adult-strength or 2 to 4 low-dose aspirin. Wait for an ambulance. Do not try to drive yourself.

Nitroglycerin. If you typically use nitroglycerin to relieve angina and if one dose of nitroglycerin has not relieved your symptoms within 5 minutes, call 911. Do not wait to call for help.

Women’s symptoms. For men and women, the most common symptom is chest pain or pressure. But women are somewhat more likely than men to have other symptoms like shortness of breath, nausea, and back or jaw pain.

Why wait for an ambulance?

By calling 911 and taking an ambulance to the hospital, you may be able to start treatment before you arrive at the hospital. If any complications occur along the way, ambulance personnel are trained to evaluate and treat them.

If an ambulance is not readily available, have someone else drive you to the emergency room. Do not drive yourself to the hospital.

CPR

If you witness a person become unconscious, call 911 or other emergency services and start CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation). The emergency operator can coach you on how to perform CPR.

To learn more about CPR, see the Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) section of the topic Dealing With Emergencies.

Who to see

Emergency medical technicians and paramedics can start treatment in an ambulance. Emergency medicine specialists evaluate and treat you in the emergency room. An interventional cardiologist or cardiovascular surgeon may perform a procedure or surgery. For care after a heart attack, you might see a cardiologist and other doctors and nurses who specialize in heart disease.

Exams and Tests

Emergency testing for a heart attack

After you call 911 for a heart attack, paramedics will quickly assess your heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing rate. They also will place electrodes on your chest for an electrocardiogram (EKG, ECG) to check your heart’s electrical activity.

When you arrive at the hospital, the emergency room doctor will take your history and do a physical exam, and a more complete ECG will be done. A technician will draw blood to test for cardiac enzymes, which are released into the bloodstream when heart cells die.

If your tests show that you are at risk of having or are having a heart attack, your doctor will probably recommend that you have cardiac catheterization. The doctor can then see whether your coronary arteries are blocked and how your heart functions.

If an artery appears blocked, angioplasty—a procedure to open up clogged arteries—may be done during the catheterization. Or you will be referred to a cardiovascular surgeon for coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

If your tests do not clearly show a heart attack or unstable angina and you do not have other risk factors (such as a previous heart attack), you will probably have other tests. These may include a cardiac perfusion scan or SPECT imaging test.

Testing after a heart attack

From 2 to 3 days after a heart attack or after being admitted to the hospital for unstable angina, you may have more tests. (Even though you may have had some of these tests while you were in the emergency room, you may have some of them again.)

Doctors use these tests to see how well your heart is working and to find out whether undamaged areas of the heart are still receiving enough blood flow.

These tests may include:

- Echocardiogram (echo). An echo is used to find out several things about the heart, including its size, thickness, movement, and blood flow.

- Stress electrocardiogram (such as treadmill testing). This test compares your ECG while you are at rest to your ECG after your heart has been stressed, either through physical exercise (treadmill or bike) or by using a medicine.

- Stress echocardiogram. A stress echocardiogram can show whether you may have reduced blood flow to the heart.

- Cardiac perfusion scan. This test is used to estimate the amount of blood reaching the heart muscle during rest and exercise.

- Cardiac catheterization. In this test, a dye (contrast material) is injected into the coronary arteries to evaluate your heart and coronary arteries.

- Cardiac blood pool scan. This test shows how well your heart is pumping blood to the rest of your body.

- Cholesterol test. This test shows the amounts of cholesterol in your blood.

Treatment Overview

Do not wait if you think you are having a heart attack. Getting help fast can save your life.

Emergency treatment gets blood flowing back to the heart. This treatment is similar for unstable angina and heart attack.

- For unstable angina, treatment prevents a heart attack.

- For a heart attack, treatment limits the damage to your heart.

Ambulance and emergency room

Treatment begins in the ambulance and emergency room. You may get oxygen if you need it. You may get morphine if you need pain relief.

The goal of your health care team will be to prevent permanent heart muscle damage by restoring blood flow to your heart as quickly as possible.

Treatment includes:

- Nitroglycerin. It opens up the arteries of the heart to help blood flow back to the heart.

- Beta-blockers. These drugs lower the heart rate, blood pressure, and the workload of the heart.

You also will receive medicines to stop blood clots. These are given to prevent blood clots from getting bigger so blood can flow to the heart. Some medicines will break up blood clots to increase blood flow. You might be given:

- Aspirin, which you chew as soon as possible after calling 911.

- Antiplatelet medicine.

- Anticoagulants.

- Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors.

- Thrombolytics.

Angioplasty or surgery

Angioplasty. Doctors try to do angioplasty as soon as possible after a heart attack. Angioplasty might be done for unstable angina, especially if there is a high risk of a heart attack.

Angioplasty gets blood flowing to the heart. It opens a coronary artery that was narrowed or blocked during the heart attack.

But angioplasty is not available in all hospitals. Sometimes an ambulance will take a person to a hospital that provides angioplasty, even if that hospital is farther away. If a person is at a hospital that does not do angioplasty, he or she might be moved to another hospital where angioplasty is available.

If you are treated at a hospital that has proper equipment and staff, you may be taken to the cardiac catheterization lab. You will have cardiac catheterization, also called a coronary angiogram. Your doctor will check your coronary arteries to see if angioplasty is right for you.

Bypass surgery. If angioplasty is not right for you, emergency coronary artery bypass surgery may be done. For example, bypass surgery might be a better option because of the location of the blockage or because of numerous blockages.

Other treatment in the hospital

After a heart attack, you will stay in the hospital for at least a few days. Your doctors and nurses will watch you closely. They will check your heart rate and rhythm, blood pressure, and medicines to make sure you don’t have serious complications.

Your doctors will start you on medicines that lower your risk of having another heart attack or having complications and that help you live longer after your heart attack. You may have already been taking some of these medicines. Examples include:

- Aldosterone receptor antagonists.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs).

- Aspirin.

- Antiplatelet medicines.

- Beta-blockers.

- Statins and other cholesterol medicines.

You will take these medicines for a long time, maybe the rest of your life.

After you go home from the hospital, take all of your medicines correctly. Do not stop taking your medicine unless your doctor tells you to. If you stop taking your medicine, you might raise your risk of having another heart attack.

Cardiac rehabilitation

Cardiac rehabilitation might be started in the hospital or soon after you go home. It’s an important part of your recovery after a heart attack. Cardiac rehab teaches you how to be more active and make lifestyle changes that can lead to a stronger heart and better health. Cardiac rehab can help you feel better and reduce your risk of future heart problems.

If you don’t do a cardiac rehab program, you will still need to learn about lifestyle changes that can lower your risk of another heart attack. These changes include quitting smoking, eating heart-healthy foods, and being active.

Quitting smoking is part of cardiac rehab. Medicines and counseling can help you quit for good. People who continue to smoke after a heart attack are much more likely than nonsmokers to have another heart attack. When a person quits, the risk of another heart attack decreases a lot in the first year after stopping smoking.

Go to your doctor visits

Your doctor will want to closely watch your health after a heart attack. Be sure to keep all your appointments. Tell your doctor about any changes in your condition, such as changes in chest pain, weight gain or loss, shortness of breath with or without exercise, and feelings of depression.

Prevention

You can help prevent a heart attack by taking steps that slow or prevent coronary artery disease—the main risk factor for a heart attack. A heart-healthy lifestyle is important for everyone, not just for people who have health problems. It can help you keep your body healthy and lower your risk of a heart attack.

Make lifestyle changes

- Quit smoking. It may be the best thing you can do to prevent heart disease. You can start lowering your risk right away by quitting smoking. Also, avoid secondhand smoke.

- Exercise. Being active is good for your heart and blood vessels, as well as the rest of your body. Being active helps lower your risk of health problems. And it helps you feel good. Try to exercise for at least 30 minutes on most, if not all, days of the week. Talk to your doctor before starting an exercise program.

- Eat a heart-healthy diet. The way you eat can help you lower your risk. There are a few heart-healthy eating plans to choose from. Remember that some foods you may hear about are just fads that don’t prevent heart disease at all.

- Comparing Heart-Healthy Diets

- Reach and stay at a healthy weight. A healthy weight is a weight that lowers your risk for health problems including heart disease. Eating heart-healthy foods and being active can help you manage your weight and lower your risk.

Manage other health problems

Manage other health problems that raise your risk for a heart attack. These include diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol. A heart-healthy lifestyle can help you manage these problems. But you may also need to take medicine.

Manage stress and get help for depression

- Manage stress. Stress can hurt your heart. Keep stress low by talking about your problems and feelings, rather than keeping your feelings hidden. Try different ways to reduce stress, such as exercise, deep breathing, meditation, or yoga.

- Get help for depression. Getting treatment for depression can help you stay healthy.

Deciding whether to take aspirin

Talk to your doctor before you start taking aspirin every day. Aspirin can help certain people lower their risk of a heart attack or stroke. But taking aspirin isn’t right for everyone, because it can cause serious bleeding.

You and your doctor can decide if aspirin is a good choice for you based on your risk of a heart attack and stroke and your risk of serious bleeding. If you have a low risk of a heart attack and stroke, the benefits of aspirin probably won’t outweigh the risk of bleeding.

For more information, see the topic Aspirin to Prevent Heart Attack and Stroke.

Learn about issues for women

Women have unique risk factors for heart disease, including hormone therapy and pregnancy-related problems. These things can raise a woman’s risk for a heart attack or stroke.

See the topic Heart Disease and Stroke in Women: Reducing Your Risk for more information on risk, symptoms, and prevention of heart disease and stroke.

Preventing Another Heart Attack

After you’ve had a heart attack, your biggest concern will probably be that you could have another one. You can help lower your risk of another heart attack by joining a cardiac rehabilitation (rehab) program and taking your medicines.

Do cardiac rehab

You might have started cardiac rehab in the hospital or soon after you got home. It’s an important part of your recovery after a heart attack.

In cardiac rehab, you will get education and support that help you make new, healthy habits, such as eating right and getting more exercise.

Make heart-healthy habits

If you don’t do a cardiac rehab program, you will still need to learn about lifestyle changes that can lower your risk of another heart attack. These changes include quitting smoking, eating heart-healthy foods, and being active.

For more information on lifestyle changes, see Life After a Heart Attack.

Take your medicines

After having a heart attack, take all of your medicines correctly. Do not stop taking your medicine unless your doctor tells you to. If you stop taking your medicine, you might raise your risk of having another heart attack.

You might take medicines to:

- Prevent blood clots. These medicines include aspirin and other blood thinners.

- Decrease the workload on your heart (beta-blocker).

- Lower cholesterol.

- Treat irregular heartbeats.

- Lower blood pressure.

For more information, see Medications.

|

One Man’s Story:  Alan, 73 “At some point in my life I was going to have a heart attack. Smoking just sped it up. It happened while I was playing basketball with some guys from work. I started getting pains in my chest. The next thing I knew, I was on the floor.”— Alan Read more about Alan and how he learned to cope after a heart attack. |

Life After a Heart Attack

Coming home after a heart attack may be unsettling. Your hospital stay may have seemed too short. You may be nervous about being home without doctors and nurses after being so closely watched in the hospital.

But you have had tests that tell your doctor that it is safe for you to return home. Now that you’re home, you can take steps to live a healthy lifestyle to reduce the chance of having another heart attack.

Do cardiac rehab

Cardiac rehabilitation (rehab) teaches you how to be more active and make lifestyle changes that can lead to a stronger heart and better health.

If you don’t do a cardiac rehab program, you will still need to learn about lifestyle changes that can lower your risk of another heart attack. These changes include quitting smoking, eating heart-healthy foods, and being active. For more information on lifestyle changes, see Prevention.

Learn healthy habits

Making healthy lifestyle changes can reduce your chance of another heart attack. Quitting smoking, eating heart-healthy foods, getting regular exercise, and staying at a healthy weight are important steps you can take.

For more information on how to make healthy lifestyle changes, see Prevention.

Manage your angina

Tell your doctor about any angina symptoms you have after a heart attack. Many people have stable angina that can be relieved with rest or nitroglycerin.

Manage stress and get help for depression

Depression and heart disease are linked. People who have heart disease are more likely to get depressed. And if you have both depression and heart disease, you may not stay as healthy as possible. This can make depression and heart disease worse.

If you think you may have depression, talk to your doctor.

Stress and anger can also hurt your heart. They might make your symptoms worse. Try different ways to reduce stress, such as exercise, deep breathing, meditation, or yoga.

Have sex when you’re ready

You can resume sexual activity after a heart attack when you are healthy and feel ready for it. You could be ready if you can do mild or moderate activity, like brisk walking, without having angina symptoms. Talk with your doctor if you have any concerns. Your doctor can help you know if your heart is healthy enough for sex.

If you take a nitrate, like nitroglycerin, do not take erection-enhancing medicines. Combining a nitrate with one of these medicines can cause a life-threatening drop in blood pressure.

Get support

Whether you are recovering from a heart attack or are changing your lifestyle so you can avoid another one, emotional support from friends and family is important. Think about joining a heart disease support group. Ask your doctor about the types of support that are available where you live. Cardiac rehab programs offer support for you and your family. Meeting other people with the same problems can help you know you’re not alone.

Take other steps to live healthier

After a heart attack, it’s also important to:

- Take your medicines exactly as directed. Do not stop taking your medicine unless your doctor tells you to.

- Do not take any over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, or herbal products without talking to your doctor first.

- If you are a woman and have been taking hormone therapy, talk with your doctor about whether you should continue taking it.

- Keep your blood sugar in your target range if you have diabetes.

- Get a flu vaccine every year. It can help you stay healthy and may prevent another heart attack.

- Get the pneumococcal vaccine. If you have had one before, ask your doctor whether you need another dose.

- Drink alcohol in moderation, if you drink. This means having 1 alcoholic drink a day for women or 2 drinks a day for men.

- Seek help for sleep problems. Your doctor may want to check for sleep apnea, a common sleep problem in people who have heart disease. For more information, see the topic Sleep Apnea.

Medications

Take all of your medicines correctly. Do not stop taking your medicine unless your doctor tells you to. Taking medicine can lower your risk of having another heart attack or dying from coronary artery disease.

In the ambulance and emergency room

Treatment for a heart attack or unstable angina begins with medicines in the ambulance and emergency room. This treatment is similar for both. The goal is to prevent permanent heart muscle damage or prevent a heart attack by restoring blood flow to your heart as quickly as possible.

You may receive:

- Morphine for pain relief.

- Oxygen therapy to increase oxygen in your blood.

- Nitroglycerin to open up the arteries to the heart to help blood to flow to the heart.

- Beta-blockers to lower the heart rate, blood pressure, and the workload of the heart.

You also will receive medicines to stop blood clots so blood can flow to the heart. Some medicines will break up blood clots to increase blood flow. You might be given:

- Aspirin, which you chew as soon as possible after calling 911.

- Antiplatelet medicine.

- Anticoagulants.

- Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors.

- Thrombolytics.

In the hospital and at home

In the hospital, your doctors will start you on medicines that lower your risk of having complications or another heart attack. You may already have taken some of these medicines. They can help you live longer after a heart attack. You will take these medicines for a long time, maybe the rest of your life.

Medicine to lower blood pressure and the heart’s workload

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs)

- Beta-blockers

You might take other medicines if you have another heart problem, such as heart failure. For example, you might take a diuretic, called an aldosterone receptor antagonist, which helps your body get rid of extra fluid.

Medicine to prevent blood clots from forming and causing another heart attack

Medicine to lower cholesterol

Other cholesterol medicines, such as ezetimibe, may be used along with a statin.

Medicine to manage angina symptoms

- Nitroglycerin

- Beta-blockers

- Calcium channel blockers

- Ranolazine (Ranexa)

What to think about

You may have regular blood tests to monitor how the medicine is working in your body. Your doctor will likely let you know when you need to have the tests.

If your doctor recommends daily aspirin, don’t substitute nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Advil, for example) or naproxen (such as Aleve), for the aspirin. NSAIDS relieve pain and inflammation much like aspirin does, but they do not affect blood clotting in the same way that aspirin does. NSAIDs do not lower your risk of another heart attack. In fact, NSAIDs may raise your risk for a heart attack or stroke. Be safe with medicines. Read and follow all instructions on the label.

If you need to take an NSAID for a long time, such as for pain, talk with your doctor to see if it is safe for you. For more information about daily aspirin and NSAIDs, see Aspirin to Prevent Heart Attack and Stroke.

Surgery

An angioplasty procedure or bypass surgery might be done to open blocked arteries and improve blood flow to the heart.

Angioplasty

Angioplasty. This procedure gets blood flowing back to the heart. It opens a coronary artery that was narrowed or blocked during a heart attack. Doctors try to do angioplasty as soon as possible after a heart attack. Angioplasty might be done for unstable angina, especially if there is a high risk of a heart attack.

Angioplasty is not surgery. It is done using a thin, soft tube called a catheter that’s inserted in your artery. It doesn’t use large cuts (incisions) or require anesthesia to make you sleep.

Most of the time, stents are placed during angioplasty. They keep the artery open.

But angioplasty is not done at all hospitals. Sometimes an ambulance will take a person to a hospital that provides angioplasty, even if that hospital is farther away. If a person is at a hospital that does not do angioplasty, he or she might be moved to another hospital where it is available.

If you are at a hospital that has proper equipment and staff to do this procedure, you may have cardiac catheterization, also called coronary angiogram. Your doctor will check your coronary arteries to see if angioplasty is right for you.

Bypass surgery

Bypass surgery. If angioplasty is not right for you, emergency coronary artery bypass surgery may be done. For example, bypass surgery might be a better choice because of the location of the blockage or because you have many blockages.

Cardiac rehabilitation

After you have had angioplasty or bypass surgery, you may be encouraged to take part in a cardiac rehabilitation program to help lower your risk of death from heart disease. For more information, see the topic Cardiac Rehabilitation.

Treatment for Complications

Heart attacks that damage critical or large areas of the heart tend to cause more problems (complications) later. If only a small amount of heart muscle dies, the heart may still function normally after a heart attack.

The chance that these complications will occur depends on the amount of heart tissue affected by a heart attack and whether medicines are given during and after a heart attack to help prevent these complications. Your age, general health, and other things also affect your risk of complications and death.

About half of all people who have a heart attack will have a serious complication. The kinds of complications you may have depend upon the location and extent of the heart muscle damage. The most common complications are:

- Heart rhythm problems, called arrhythmias. These include heart block, atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation.

- Heart failure, which can be short-term or can become a lifelong condition. Scar tissue eventually replaces the areas of heart muscle that are damaged by a heart attack. Scar tissue affects your heart’s ability to pump as well as it should. Damage to the left ventricle can lead to heart failure.

- Heart valve disease.

- Pericarditis, which is an inflammation around the outside of the heart.

Treatment for heart rhythm problems

If the heart attack caused an arrhythmia, you may take medicines or you may need a cardiac device such as a pacemaker.

If your heart rate is too slow (bradycardia), your doctor may recommend a pacemaker.

If you have abnormal heart rhythms or if you are at risk for abnormal heart rhythms that can be deadly, your doctor may recommend an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD).

For information on different types of arrhythmias, see:

Palliative care

Palliative care is a kind of care for people who have a serious illness. It’s different from care to cure your illness. Its goal is to improve your quality of life—not just in your body but also in your mind and spirit. You can have this care along with treatment to cure your illness.

Palliative care providers will work to help control pain or side effects. They may help you decide what treatment you want or don’t want. And they can help your loved ones understand how to support you.

If you’re interested in palliative care, talk to your doctor.

For more information, see the topic Palliative Care.

End-of-life care

Treatment for a heart attack is increasingly successful at prolonging life and reducing complications and hospitalization. But a heart attack can lead to problems that get worse over time, such as heart failure and abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias).

It can be hard to have talks with your doctor and family about the end of your life. But making these decisions now may bring you and your family peace of mind. Your family won’t have to wonder what you want. And you can spend your time focusing on your relationships.

You will need to decide if you want life-support measures if your health gets very bad. An advance directive is a legal document that tells doctors how to care for you at the end of your life. You also can say where you want to have care. And you can name someone who can make sure your wishes are followed.

For more information, see the topic Care at the End of Life.

References

Other Works Consulted

- Abraham NS, et al. (2010). ACCF/ACG/AHA 2010 Expert consensus statement on the concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and thienopyridines: A focused update of the ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 Expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Published online November 8, 2010 (doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.010).

- Amsterdam EA, et al. (2014). 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Circulation, 130(25): e344–e426. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000134. Accessed October 24, 2014.

- Bhatt DL, et al. (2008). ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 Expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation, 118(18): 1894–1909.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2016). Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 164(12): 836–845. DOI: 10.7326/M16-0577. Accessed May 16, 2017.

- De Lemos JA, et al. (2011). Unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. In V Fuster et al., eds., Hurst’s the Heart, 13th ed., vol. 2, pp. 1328–1353. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Eckel RH, et al. (2013). 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/early/2013/11/11/01.cir.0000437740.48606.d1.citation. Accessed December 5, 2013.

- Fleg JL, et al. (2013). Secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in older adults: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, published online October 28, 2013. DOI: 10.1161/01.cir.0000436752.99896.22. Accessed November 22, 2013.

- Hass EE, et al. (2011). ST-segmented elevation myocardial infarction. In V Fuster et al., eds., Hurst’s the Heart, 13th ed., vol. 2, pp. 1354–1385. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Hendel RC, et al. (2009). ACCF/ASNC/ACR/AHA/ASE/SCCT/SCMR/SNM 2009 appropriate use criteria for cardiac radionuclide imaging. Circulation, 119(22): e561–e587.

- Holmes DR, et al. (2010). ACCF/AHA Clopidogrel clinical alert: Approaches to the FDA “Boxed Warning”: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association. Circulation, 122(5): 537–557.

- Jneid H, et al. (2017). 2017 AHA/ACC clinical performance and quality measures for adults with ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 10(10): e000032. DOI: 10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000032. Accessed September 25, 2017.

- Levine GN, et al. (2011). 2011 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation, 124(23): e574–e651.

- Levine GN, et al. (2012). Sexual activity and cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 125(8): 1058–1072.

- Levine GN, et al. (2015). 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI Focused update on primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: An update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation, published online October 15, 2015. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000336. Accessed October 16, 2015.

- Lichtman JH, et al. (2008). Depression and coronary heart disease: Recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: A science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: Endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation, 118(17): 1768–1775.

- Malenka DJ, et al. (2008). Outcomes following coronary stenting in the era of bare-metal vs the era of drug-eluting stents. JAMA, 299(24): 2868–2876.

- O’Connor RE, et al. (2010). Acute coronary syndromes: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation, 122(18): S787–S817.

- O’Gara PT, et al. (2013). 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: Executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 127(4): e362–e425.

- Rosendorff C, et al. (2015). Treatment of hypertension in patients with coronary artery disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Society of Hypertension. Circulation, 131(19): e435–e470. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000207. Accessed March 31, 2015.

- Skinner JS, Cooper A (2011). Secondary prevention of ischaemic cardiac events, search date May 2010. BMJ Clinical Evidence. Available online: http://www.clinicalevidence.com.

- Smith SC, et al. (2011). AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: A guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation, 124(22): 2458–2473. Also available online: http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/124/22/2458.full.

- Somers VK, et al. (2008). Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: An American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing in collaboration with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Center on Sleep Disorders Research (National Institutes of Health). Circulation, 118(10): 1080–1111.

- Thygesen K, et al. (2012). Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation, 126(16): 2020–2035. Also available online: http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/126/16/2020.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2009). Using nontraditional risk factors in coronary heart disease risk assessment. Available online: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspscoronaryhd.htm.

- Wakai A (2011). Myocardial infarction (ST-elevation), search date October 2009. Online version of BMJ Clinical Evidence: http://www.clinicalevidence.com.

Current as of: April 9, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:Kathleen Romito MD – Family Medicine & E. Gregory Thompson MD – Internal Medicine & Martin J. Gabica MD – Family Medicine & Adam Husney MD – Family Medicine & Elizabeth T. Russo MD – Internal Medicine & George Philippides MD – Cardiology

How a Heart Attack Happens

How a Heart Attack Happens Angina Symptoms

Angina Symptoms The heart and the coronary arteries

The heart and the coronary arteries Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis Cardiac catheterization laboratory

Cardiac catheterization laboratory Coronary Stent

Coronary Stent How to Prevent a Second Heart Attack

How to Prevent a Second Heart Attack Is It a Heart Attack?

Is It a Heart Attack? Why Beta-Blockers Are Important After a Heart Attack

Why Beta-Blockers Are Important After a Heart Attack Statins Are Important After a Heart Attack

Statins Are Important After a Heart Attack Cardiac Rehab: What Is It?

Cardiac Rehab: What Is It?

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.